Follow Us

Follow Us Like Us

Like Us

https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Harvey_Sir_John_ca_1581_or_158...

Sir John Harvey was a royal governor of Virginia who was ousted from office by a powerful faction in the governor's Council. Charles I appointed Harvey, a ship owner and councilor, in 1628. While he oversaw a dramatic increase in population and production, conflicts between himself and the Council defined his regime. The largest in a series of disputes involved the nature of Virginia's government, which had been brought under royal authority. Harvey understood that his instructions gave him full control over the colony with the Council acting as an advisory body, while the councilors felt he could not act without their consent. His aggressive manner further alienated its members. In the spring of 1635 an official protest against a planned tobacco monopoly brought their tensions into direct conflict. On April 28 both Harvey and the Council attempted to arrest each other on charges of treason. The councilors, backed by musketeers, prevailed. Charles I reappointed him as a means of asserting royal power, but Harvey's opponents eventually engineered a second removal in favor of former Governor Sir Francis Wyatt. Harvey remained in Virginia for several more years, but was in debt and had much of his property seized. He died in England sometime before July 16, 1650.

Early Years

Harvey was born sometime around 1581 or 1582. A ship master and owner, he may have been of the Harvey family that was prominent in the Dorsetshire town of Lyme Regis on the south coast of England. His younger brother, Simon Harvey, became principal procurer of food and wines for the household of James I in 1621 and was knighted two years later. Whether as a young man John Harvey married or had children is not known. By the beginning of the 1620s he had transported a large number of people to Virginia for the Virginia Company of London, which in 1622 granted him a tract of land in the colony. Harvey had enough political connections that in the autumn of 1623 the king appointed him chair of a royal commission to investigate conditions in the colony. Harvey's was the second in a series of commissions concerning the colony but the only one to conduct its investigation in Virginia.

The commissioners reported in the spring of 1624 that the population was larger and in better condition than anticipated but that arms and munitions were in short supply. They predicted that if more colonists and armed men went to Virginia promptly the colony would be able to flourish within two or three years and the Indians of Tsenacomoco could be subdued. The commissioners also took note of very intense dissatisfaction in the colony with some company officials in England. Harvey remained in Virginia for several months to look after his property and to load a cargo of tobacco for the return voyage.

James I revoked the charter of the Virginia Company on May 24, 1624, well before he received even the preliminary version of the commissioners' report. Later in the year he authorized the company's last governor, Sir Francis Wyatt, to return to England on personal business and named Sir George Yeardley to serve as governor during the interim. The authorization designated Harvey a member of the governor's Council and provided that in the event of Yeardley's death during Wyatt's absence Harvey would become governor. Harvey may have left Virginia before learning of the appointment and almost certainly did not serve on the Council during the 1620s.

Governor

James I died late in March 1625, and on May 13, Charles I made Virginia a royal colony and later in the year appointed Yeardley governor and reappointed the Council members, including Harvey. On March 26, 1628, the king appointed Harvey governor of Virginia and probably also knighted him, as references to him as Sir John Harvey first appear at that time. Harvey remained in England for a year and a half, negotiating his salary and perquisites, waiting for additional instructions, and renting a ship. In keeping with the recommendations of the commission he had chaired, Harvey pleaded for supplies and for men and arms to fortify Point Comfort in order to protect the colony from the Spanish and tried to persuade the king to send fifty armed men annually for three years. He also urged officials of the city of London to send 100 poor boys and girls and tried to hire several ministers to make the voyage with him and settle in Virginia.

The dates of Harvey's arrival in Jamestown and his assumption of the duties of governor are not preserved in extant records. After recovering from a serious illness that he contracted on the voyage or during an early hot spell soon after his arrival, he summoned and presided at a General Assembly that convened on March 24, 1630, the earliest date on which his name appears in surviving records as governor. Harvey found that little had changed since he left in 1624. The colony was still in a poor state of defense, and he had to send out ships to purchase foodstuffs pending the harvest of grain that he immediately ordered planted.

In spite of recurrent disagreements with various members of the Council during his first five years as governor, Harvey presided over the colony at a period of substantial improvement in its prospects and economy. Between 1630 and 1635 the white population of the colony grew from about 2,500 people to more than 5,000. Harvey negotiated a peace with the Algonquian-speaking Indians of Tsenacomoco and within four years completed construction of a palisade across the Peninsula between the York and James rivers (passing through the site of the later city of Williamsburg). The palisade appeared to offer a measure of protection to a large proportion of the colony's white residents, and it also safely confined most of the colonists' cattle and swine, which ranged freely in the woods. In part because of Harvey's insistence on planting cereals, in 1633 Virginians shipped 5,000 bushels of surplus grain to colonists in New England. Moreover, legislation passed in 1632 and 1633 established regular quarterly meeting dates for the colony's principal court in Jamestown and authorized monthly courts in various parts of the colony to undertake important new local responsibilities, furthering the development of Virginia's county court system.

The laws that the General Assembly adopted, and that Harvey approved while he was governor, cover a wide range of subjects and suggest that on some important matters of public policy he and the Council members and burgesses initially agreed. Assembly sessions in 1630, 1632, 1633, and 1634 all adopted measures to increase the planting of cash crops other than tobacco, as well as production of foodstuffs, potash, and iron ore. In the first of a series of acts that the king insisted on, and that Harvey pushed through, to reduce the colony's dependence on tobacco, the assembly limited annual tobacco cultivation to 2,000 plants per laborer. The assembly renewed old laws ordering that inferior tobacco be burned to prevent leaf of poor quality from depressing the price of good tobacco and also requested the king to forbid tobacco cultivation in England to reduce competition for Virginia tobacco.

The veteran members of the governor's Council who were in office when Harvey arrived were shrewd men with powerful connections to London mercantile houses that dominated the export of tobacco from Virginia. Samuel Mathews and William Claiborne, in particular, hoped to revive the Virginia Company or reconstitute it in some manner in order to continue controlling the tobacco trade. Harvey's relationship with them began to deteriorate during the first year of his administration. His quick temper and habit of issuing orders without consultation and requiring obedience without question were undoubtedly in part responsible. Rumors that the king had not settled on the form of the colony's governance and that he contemplated creating a royal monopoly on the tobacco trade made them fearful and suspicious of the king's governor. Harvey also alienated them and annoyed the king early on by encouraging the independent sale of tobacco to New Netherlands merchants. Council members also feared that the king or governor might invalidate their land titles, as had been done in Ireland.

As the king's personal appointee and representative, Harvey understood that his royal commission gave him full authority to govern the colony and that the Council existed primarily to offer him advice; but the Council members insisted that governors had been and should remain merely presiding officers at Council meetings with only a casting vote to break ties and that they could not act at all without the Council's consent. In December 1631, Harvey agreed to accept the Council's interpretation, but he repeatedly and without success appealed to the king to strengthen his hand by publicly endorsing his own reading of the commission.

The governor and Council members began to argue again in 1633 and 1634 when Harvey, under orders from the king, offered assistance to the first settlers of Maryland, many of whom were Catholics and occupied land formerly within the boundaries of Virginia. Prejudice against Catholics produced fear and resentment in Virginia, and because Harvey assisted the immigrants as the king commanded, his reputation suffered.

'Thrust Out' of Office

Opposition to Harvey coalesced and spread in the spring of 1635 after planters and political leaders learned that the governor had not sent to London the General Assembly's signed protest against the king's plan for a royal monopoly on the tobacco trade. All the burgesses and Council members signed the document, including burgesses who opposed restoring the company and wanted to sell tobacco to the Dutch. Harvey sent a copy to the king's principal secretary of state but kept the signed original in Jamestown. His days in office were numbered when it became known that he had obstructed the General Assembly's direct appeal to the king on behalf of all the tobacco planters in Virginia.

Opponents of Harvey circulated a statement of complaint, reportedly with the approval of some Council members, and obtained signatures in several areas of Virginia. Harvey arrested several opponents and summoned the Council into session on April 27. That meeting broke up after angry arguments. At a meeting on April 28, 1635, the arguments resumed, and Harvey and members of the Council arrested each other on charges of treason. Armed musketeers then rushed out of the woods and surrounded the governor's house. Using a provision of the king's commission, the Council members then elected one of their own, John West, as governor. The Council called the General Assembly back into session on May 7 to state its objections to Harvey and restate its objections to the tobacco monopoly. The assembly met despite Harvey's declaration that the meeting was illegal. Opposition to Harvey was by then almost unanimous and only one or two Council members were not in Jamestown at the time of the coup d'état. It became clear to Harvey that he had few or no options, and he departed for England later in the month under the guard of Mathews and Francis Pott.

The arrest and expulsion of the governor became known in the literature of Virginia's history as the thrusting out of Sir John Harvey. The phrase came into use after 1809 when in volume one of his edition of The Statutes at Large, William Waller Hening printed some seventeenth-century notes taken from documents now lost recording that Harvey had been "thrust out" of office.

Governor Again

When Harvey arrived in Plymouth, England, in July 1635, he had Mathews and Pott arrested and began an energetic campaign to recover his office. It was not until December 11 that Harvey personally presented his case to the king and Privy Council. Notes made by a clerk quoted the king as saying that he had to send Harvey back as governor even if for only one day. The king's comment was more in the nature of an assertion of his own authority than of confidence in Harvey because he also hinted that how long Harvey retained the governorship would depend on how well he did.

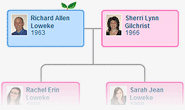

After many delays, Harvey returned to Virginia on January 18, 1637, and immediately resumed the office of governor. On an unrecorded date between September 23, 1637, and May 11, 1639, he married Elizabeth Peirsey Stephens, daughter of Abraham Peirsey, who had served with him on the commission in the 1620s, and widow of Council member Richard Stephens. They had two daughters. (Her son, Samuel Stephens, was later a governor of Albemarle, also known as Carolina and later as North Carolina, and was also the first husband of Frances Culpeper Stephens Berkeley Ludwell, whose second husband was Virginia governor Sir William Berkeley.)

Harvey's second administration was shorter and less notable than his first. It was somewhat less contentious but much less well documented. Harvey resumed, without much success, trying to implement the king's orders to reduce tobacco cultivation and to eliminate trade with Dutch merchants. Harvey's old adversaries remained actively opposed to him and he made new enemies. He banished a colonist for speaking disrespectfully about him, and when a clergyman incurred Harvey's displeasure, the governor banished him and confiscated his property. In London, Mathews and his allies mounted a sustained and vigorous campaign against Harvey that eventually earned them a royal pardon and restoration of the property that the governor had tried to sequester. Harvey's advocates, including Council member George Donne, who returned to England to argue Harvey's case, were not successful. Instead, Mathews and his allies persuaded the king and Privy Council to replace Harvey with former governor Sir Francis Wyatt.

Later Years

During the first months following Wyatt's arrival and installation as royal governor in November 1639, Harvey attended some meetings of the Council, and he remained in the colony as late as May 1640 and possibly later. Badly in debt and widely despised, he suffered the humiliation of having much of his property confiscated and sold to pay some of his many debts. The following year Harvey sold his spacious residence in Jamestown to the colony. In his final surviving letter from Virginia, written on May 6, 1640, he portrayed himself as persecuted, impoverished, and pitiable, asking only that he be allowed to leave before he was irretrievably ruined financially.

Harvey was certainly not a good choice for governor. He lacked the tact and subtlety to prevail against Mathews and Claiborne, and he alienated most of the men whose support he needed. The failure of the king and his ministers to pay Harvey's salary forced him to borrow money from the people he was supposed to govern, which weakened his political standing. The king's protracted indecision about the final form of government for the colony and his inability through the governor to reassure the colony's planters about the security of their land titles also seriously undermined Harvey's own limited ability to navigate successfully the turbulent and unpredictable political waters that he frequently stirred up in Virginia during the 1630s.

After he returned to England in 1640, Harvey may have settled into retirement in London, but as with other aspects of his personal life little is well documented about his final decade. His wife died by September 15, 1646, because Harvey did not mention her when he wrote his will before departing on a planned ocean voyage to an unstated destination. The will included a complaint that the king still owed him £5,500, perhaps Harvey's unpaid salary from his second term as governor, and mentioned about £2,000 in debts due to him from people in the colony. The will provided comfortably (if all the debts could be collected) for his daughters and for the orphaned son and two daughters of his brother, Sir Simon Harvey. The will also left £400 to the poor of the London parish of Saint Dunstan in the West, which is where he may have then resided. The date and place of Harvey's death and burial are not known, but he certainly died before July 16, 1650, when the will was proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury.

Time Line

ca. 1581 or 1582 - John Harvey is born in England.

Early 1620s - By this time, John Harvey has transported a large number of people to Virginia for the Virginia Company of London.

1622 - The Virginia Company of London grants John Harvey a tract of land in Virginia.

Autumn 1623 - James I appoints John Harvey chair of a royal commission to investigate conditions in the Virginia colony.

1624 - James I authorizes Governor Sir Francis Wyatt to return to England on personal business and names Sir George Yeardley to serve as governor in the interim. He also designates John Harvey a member of the governor's Council and provides that in the event of Yeardley's death during Wyatt's absence, Harvey will become governor.

May 24, 1624 - Following a yearlong investigation into mismanagement headed by Sir Richard Jones, justice of the Court of Common Pleas, the Crown revokes the Virginia Company of London's charter and assumes direct control of the Virginia colony.

March 26, 1628 - King Charles I appoints John Harvey governor of Virginia and probably also knights him.

March 24, 1630 - Sir John Harvey summons and presides at the General Assembly that convenes on this date. It is the earliest date on which his name appears in surviving records as governor.

December 1631 - Sir John Harvey accepts the governor's Council's interpretation of the role of governor: that the governor should remain merely a presiding officer at Council meetings with only a casting vote to break ties.

April 28, 1635 - Sir John Harvey and members of the governor's Council attempt to arrest each other on charges of treason.

May 7, 1635 - The General Assembly meets to state its objections to Governor Sir John Harvey and to restate its objections to the royal monopoly on tobacco. The governor's Council elects one of their own, John West, as governor.

July 1635 - Former governor Sir John Harvey arrives in Plymouth, England, has Samuel Mathews and Francis Pott arrested, and begins a campaign to recover his office.

December 11, 1635 - Sir John Harvey presents to the king and Privy Council the case for his reinstatement as governor of Virginia.

January 18, 1637 - Sir John Harvey returns to Virginia and resumes the office of governor.

September 23, 1637–May 11, 1639 - During this period, Sir John Harvey marries Elizabeth Peirsey Stephens, daughter of Abraham Peirsey and widow of Richard Stephens. They will have two daughters.

November 1639 - Sir Francis Wyatt replaces Sir John Harvey as governor of Virginia.

1640 - Sir John Harvey returns to England.

September 15, 1646 - Elizabeth Peirsey Stephens Harvey, wife of Sir John Harvey, has died by this date.

July 16, 1650 - Sir John Harvey's will is proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The records of Virginia have given some of the history and family connections of Governor John Harvey. He was of [Lyme Regis], Dorset, was captain of a ship in the East Indies 1617-19; came to Virginia early in 1624, as one of the commissioners appointed by the King to examine into the condition of the Colony; appointed member of the Council August, 1624; shortly after returned to England, and in November, 1625, commanded a ship in the expedition against Cadiz; continued to serve in the navy for several years; he was appointed Governor of Virginia, knighted, and arrived in the Colony early in 1630," ["Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents," Virginia Historical Magazine, Vol. 1, pg. 87.] Governor Harvey, while he was in Virginia, married the widow of Richard Stephens in 1638. She was formerly Elizabeth Persey (born about 1609), daughter of Abraham Persey (member of the Council). The Governor was 54 years old at the time of his marriage to Elizabeth. ["Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents," Virginia Historical Magazine, Vol. 1, pg. 82-83; and Adventurers of Purse and Person VIRGINIA 1607-1624/5, 1987, p. 481].

Sir John Harvey left a Will, dated 15 Sept. 1646 and proved 16 July 1650 in London, which gave some of his English family connections. The Will, [Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 18, pg. 306], stated: "I am now bound on a voyage to sea. The King owes me £5500 as appears under account of Mr. Orator Bingley and Sir Paul Pinder, and several persons in Virginia owe me £2000. I owe Tobias Dixon citizen and Haberdasher of London, £1000, and Mr. Nickolls of London, Ironmonger, £200. To Ursilla, my eldest daughter £1000. To Anne my daughter £1000. If my daughters die without issue, £500 to my nephew Simon, son of my Brother the late Sir Simon Harvey of London, knt., and £400 to his two daughters and £400 to poor of St. Dunstans in the West. Executor: Tobias Dixon. Witnesses: Miles Arundell, Henry Wagstaffe, Thomas Smith, servant to Arthur Tirey Sr., Thomas Bland, Roger Escame."

______________

_________________________

| 1582 |

1582

|

Lyme Regis, Dorset, England, United Kingdom

|

|

| 1638 |

1638

|

||

|

1638

|

|||

| 1650 |

July 16, 1650

Age 68

|

England, United Kingdom

|