Follow Us

Follow Us Like Us

Like Us

public profile

http://www.maryrangallery.com/artists/elizabeth_boott_duveneck

Biography

Elizabeth Boott Duveneck (American/Boston 1846-1888)

Elizabeth Boott Duveneck's life reads like a Jamesian novel. She was, in fact, along with her widowed father, a model for characters in "Portrait of a Lady" (1881), "The Golden Bowl" (1904) and several other novels and stories by Henry James.

Elizabeth, known always as Lizzie, was raised in a privileged and cosmopolitan environment. Her mother, Elizabeth Lyman Boott, was the eldest daughter of Boston Brahmin George Lyman and his first wife, the daughter of Harrison Gray Otis. Her father, Francis Boott, was a composer and music critic. Mrs. Boott, like so many others of her generation, suffered from lung trouble. At the advise of the family's physician, her husband took her south, hoping the warmer climate of Charleston might prove beneficial. Unfortunately, the disease was too far advanced, and in 1847 she passed away, leaving behind a deeply bereaved husband and an eighteen month old daughter.

The social climate in mid-nineteenth century Boston was not felicitous for the arts, and Boott found himself at odds with the society to which he belonged. Shortly after his wife's death, he took Lizzie to Europe. There they divided their seasons between various locations, eventually settling in the Villa Castellani at Bellosguardo, overlooking Florence. As part of that city's Anglo-American community, the Bootts enjoyed a companionable life dominated by music, painting, good food and lively conversation.

Francis Boott undertook for himself the serious study of musical composition and saw to it that his young daughter had lessons in everything: piano, voice, violin, French, Italian, Latin, drawing, painting, riding and swimming.

Lizzie's interest in drawing was encouraged by her father, who carefully preserved all of her early sketches and watercolors. In 1865 the Bootts returned to Boston, where nineteen-year-old Lizzie became friends with Alice, William and especially Henry James, who found her infinitely "civilized and produced...educated, cultivated, accomplished, toned above all, as from steeping in a rich old medium."

The James and Boott families spent part of the summer of 1869 together at a farmhouse in Pomfret, New York. Through this association, Lizzie came to know William Morris Hunt and entered the class for women artists he was just forming in Boston. Hunt was an influential artist and critic, whose modern French aesthetic principles were the antithesis of traditional academic methods. His richly painted landscapes and his proselytizing for French paintings by the Barbizon School inspired and movement among Boston artists, setting them against the realist style of the Hudson River School, which still prevailed in New York.

Taught by Hunt to admire the Barbizon tradition of painting directly from nature, Lizzie viewed Corot and Millet as the greatest of modern masters. While in Boston Lizzie attended an exhibition of the radical new Midwestern painter Frank Duveneck and was sufficiently impressed to buy a portrait. In 1880, while studying with Thomas Couture at Villiers-le-Bel, France, she took a side trip to Venice to seek out Duveneck, and decided to work with him as a private student in Munich the following summer. During this tutelage, the two fell in love, to the horror of Lizzie's father, who considered Duveneck a fine artist, but a boorish individual, totally unsuitable for his well-bread daughter. Henry James was also displeased. He later wrote "For him it is all gain, for her it is very brave."

Though Lizzie and Duveneck continued to see each other, they did not marry until 1886. In the interim, she applied herself to her work with ever greater concentration, keeping up a full schedule of painting and exhibiting. Her first show was a joint one with fellow artist Annie Dixwell in Boston at J. Eastman Chase's Gallery. This was followed by submission throughout 1883 to the American Watercolor Society, the Boston Art Club, the Society of American Artists, the Pennsylvania Academy, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Society of Artists.

A trip that year to the American South produced five portraits of black farm works and two genre scenes, both with the same title. All these endeavors culminated in a large, well received one-person show at Doll and Richards Gallery in Boston in 1884.

On March 25, 1886, despite her father's concerns, Lizzie Boott and Frank Duveneck were married before a justice of the peace in Paris. After their wedding, they painted and lived with her father at the Villa Castellani. Remembering the death of his own wife forty years earlier, Francis Boott was anxious when his daughter became pregnant at the age of forty. After the birth of her son in December 1886, Lizzie wrote, "It seems strange after so many years of spinsterhood to get so much domestic life in so short a time." And Later, "I am beginning to work again, though not very steadily for the baby is very absorbing. I find that I am constantly thinking about him and wondering in my ignorance if everything is done that ought to be."

In October 1887, in search of more artistic opportunities for Duveneck, the couple moved to Paris. Lizzie, was busy with the baby, household tasks and long hours posing for Frank's full-length portrait of her (which was intended for the Paris Salon), caught a chill in the cold Parisian winter. Her ailment rapidly developed into pneumonia, and four days later she died, leaving Duveneck alone with their twenty-month old son. At the insistence of Francis Boott, the child was sent to relatives in Boston who could ensure his proper upbringing.

Frank Duveneck returned to Cincinnati. He sculpted a memorial to his wife, a bronze version of which was placed at her tomb in Florence's Allori Cemetery in 1891. Francis Boott so admired this personification of his daughter that he asked Duveneck to create a marble version to be displayed in Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, where Lizzie's son and her many friends might see it.

http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/narcissus-on-the-campagna-35592

Lizzie Boott’s nearly two years in Rome, from 1871 to 1873, mark a highlight of her career. Then in her mid-twenties, Boott had been painting and drawing for two decades, as evidenced by the profusion of drawings, watercolors, and illustrations she had made from childhood on. Boott, whose mother died when she was eighteen months old, spent most of her youth in Italy with her father Francis Boott, whose family’s wealth came from manufacturing. Part of a large American expatriate community, the Bootts lived near Florence in the Villa Castellani at Bellosguardo. In 1865, father and daughter returned to Boston, Massachusetts, where Lizzie began to study painting with William Morris Hunt link in a class he offered for aspiring women artists, one of the first opportunities American women had been given to study the craft. Lizzie and her father returned to Italy in 1871, now basing themselves mainly in Rome, where Lizzie maintained a studio at the Piazza Barberini. In March 1873, writer and family friend Henry James, together with artists Edward Darley Boitlink and Frederic Crowninshieldlink, made a visit to Boott’s studio where she showed them her work, including a group of sepia and watercolor sketches. James reported that they “were much surprised at her fertility, inventiveness and general skill.” He added, “She ought now to paint . . . to sell her things and make herself, if she wishes a career.”link

Narcissus on the Campagna, with its quickly brushed technique and its palette of somber browns, grays, and greens contrasting with the white blossoms, suggests the strong influence of William Morris Hunt, who encouraged his students to capture broad effects rather than meticulous details. Its vertical composition and the subject itself relate to John La Farge’s work (seeHollyhocks and Corn link), which Boott also knew. Her composition emphasizes the growing narcissus, but it also contains an unmistakable reference to Rome in the tiny, shadowed dome of St. Peter’s on the horizon. The Campagna, which had meant so much to artists of earlier generations, still had resonance for American painters and writers. Boott frequently described horseback riding on the Campagna alone or in company with such friends as James and Alice Bartlett; linkthey would “make expeditions on the Campagna, sketch by the hours, ride till after the sun had set in red and gold behind the great dome and the mysterious twilight hour had begun.”link

James, describing spring coming to Rome, wrote: “Far out on the Campagna, early in February, you felt the first vague, earthy emanations . . . It comes with the early flowers, the white narcissus and the cyclamen, the half-buried violets and the pale anemones, and makes the whole atmosphere ring.”link He also often referred in his letters to his rides on the Campagna with Boott during her sojourn in Rome, when Narcissus on the Campagna was executed. link Perhaps finished in the studio, this may be the kind of study Boott referred to when she wrote, “the Campagna gives one ever new and varied effects for memory sketches, and I have often blessed Mr. Hunt who first made me exert my memory in this way.” linkThe painting was exhibited in New York at the National Academy in March 1876.

Boott’s career was cut short by an early death. She is buried in Florence, in a tomb effigy designed by her husband, painter Frank Duveneck, a marble version link of which is in the Museum’s collection.

Notes 1.(Henry James to his mother, Mrs. Henry James, Sr., March 24, 1873, quoted in Henry James Selected Letters, ed. Leon Edel (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1987), 108. 2. Alice Bartlett (d. 1912), who later married her cousin Henry Edward Warren, wrote magazine articles about her travels in Europe, provided Henry James with the germ of the story that inspired Daisy Miller, and was also a friend of Louisa and May Alcott. See Daniel Shealy, ed. Little Women Abroad: The Alcott Sisters’Letters from Europe, 1870–1871(Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008), lxii. 3. Elizabeth Boott to members of William Morris Hunt’s art class, Rome, December 6, 1877, Cincinnati Historical Society, Ohio. 4. Henry James, “Roman Rides,” Transatlantic Sketches (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875), 150. 5. Henry James to his father, Henry James, Sr., March 4, 1873, Rome, quoted in Edel, Henry James Selected Letters, 99. 6. Elizabeth Boott to members of William Morris Hunt’s art class, Rome, January 6, 1878, Cincinnati Historical Society, Ohio.

This text has been adapted from Susan Ricci’s entry in The Lure of Italy: American Artists and the Italian Experience, 1760–1914, by Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., et al., exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1992).

Elizabeth Boott From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Elizabeth "Lizzie" Otis Lyman Boott (April 13, 1846 – March 22, 1888) was an American artist.

Boott was born on April 13, 1846 in Boston, Massachusetts. She was the daughter of the classical music composer, Francis Boott and Elizabeth (nee Lyman) Boott. Her mother, who died when she was 18 months old, was the eldest daughter of a Boston Brahmin, George Lyman and his first wife, who was the daughter of Harrison Gray Otis.[1][2]

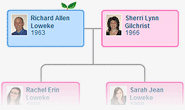

On March 25, 1886, in Paris, she married artist Frank Duveneck, who had been one of her teachers. Following their wedding, they lived at the Villa Castellani with her father. Their son, Frank Boott Duveneck was born on December 18, 1886. He became an engineer and married Josephine Whitney, the daughter of Henry M. Whitney.[1][2][3]

Boott lived in Italy, where she had long resided in Bellosguardo, overlooking Florence. She lived later in Paris with her husband and son. She died there on March 22, 1888, of pneumonia.[1][3]

Professional background

Boott was a model for characters in two Henry James novels, Portrait of a Lady and The Golden Bowl.[2][4]

Boott studied for several years with William Morris Hunt in Boston and Thomas Couture of Villiers-le-Bel in Paris. Her first show was held in Boston at J. Eastman Chase's Gallery.[1][2][4]

Elizabeth Boott. (2014, January 16). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22:27, July 11, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Elizabeth_Boott&oldid=591...

http://www.dearhenryjames.org/cast_of.html

Boott (Duveneck), Elizabeth (Lizzie) (1846-1888), and her father, Francis Boott (1813-1904), were friends of the Temples and of the Jameses. Henry James was particularly close to them. Lizzie’s talent as an artist was recognized early, and she pursued this passion all her life. One of her teachers was Frank Duveneck, whom she married in 1886. Henry James supported and promoted her career as an artist, and often visited the Bootts at Bellosguardo, their Italian home. Lizzie is said to be the model for Pansy Osmond in The Portrait of a Lady. She died in childbirth.

| 1846 |

April 13, 1846

|

Boston, Suffolk County, Massachusetts, United States

|

|

| 1886 |

December 18, 1886

|

Florence, Florence, Tuscany, Italy

|

|

| 1888 |

March 22, 1888

Age 41

|

Florence, Metropolitan City of Florence, Tuscany, Italy

|

|

|

1888

Age 41

|

Florence Allori Cemetery, Florence, Florence, Tuscany, Italy

|