Follow Us

Follow Us Like Us

Like Us

Manrique Pérez de Lara (muerto en Huete, 9 de julio de 1164), primer señor de Molina, fue el noble más importante y poderoso de su época como regente de Castilla. Hijo del conde Pedro González de quien heredó la jefatura de la casa de Lara, participó activamente en los acontecimientos políticos del reino así como en la epopeya de la reconquista y repoblación de las tierras bajo el control de los musulmanes. Se enfrentó al rey Fernando II de León y a los miembros de la casa de Castro por la custodia del infante Alfonso cuando este quedó huérfano en 1158 tras la muerte de su padre, el rey Sancho III, con lo que evitó que el rey niño —como heredero de la corona castellana— prestara homenaje vasallático al rey leonés.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manrique_P%C3%A9rez_de_Lara

Manrique Pérez de Lara

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

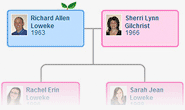

Manrique Pérez de Lara (died 1164) was a magnate of the Kingdom of Castile and its regent from 1158 until his death. He was one of the most important counsellors and generals of three successive Castilian monarchs: Alfonso VII (1126–57), Sancho III (1157–58) and Alfonso VIII (1158–1214). He was a leading figure of the House of Lara and the ancestor and namesake of the Manrique branch of the family.

Manrique's father was Pedro González de Lara (died 1130). Of Pedro's rule and Manrique's succession to his position of honour and leadership in the Reconquista, a contemporary writes:

He took after his father in everything that he did. His father was Count Pedro of Lara, who ruled his own land for many years. The son also follows in all his father's footsteps. Still in the flower of youth, but enriched with honour and respected by the Emperor as is his nature, he was the upholder of the law, the worst scourge of the Moors.

Manrique's mother, Eva, may have been the daughter of Pedro Fróilaz de Traba, but there is precious little concerning her origins and she may have been French, as the name she gave her son was of French origin (from Latin Almanricus/Amalricus, French Amaury).

The first mention of Manrique's parents' marriage dates from November 1127, and must have occurred after 1108. Manrique had three brothers: Álvaro, Nuño and Rodrigo. He had a younger full sister, Mayor, and two half-siblings, Elvira and Fernando, children of his father's liaison with Queen Urraca.

Between 26 December 1134 and 2 June 1137 Manrique served as alférez, that is, head of the military household, of Alfonso VII. This post was usually reserved for young noblemen with promising career prospects. In 1143 Manrique was granted the tenencia (or honor, a fief governed on behalf of the crown) of Atienza, and in 1144 he received those of Ávila, Madrid and Toledo. Madrid he only governed until the next year (1145) and Ávila until 1150. On 21 August 1145 Manrique was made a count, the highest rank in the kingdom, by Alfonso VII in the ancient capital city of León. A charter survives that reads: "Manrique the same day this charter was made was made a count". Althought it was common for aristocratic sons to accede to the titles of their fathers on the latters' deaths, Manrique had to wait fifteen years to receive the comital title from the king. While he continued to Atienza and Toledo, he also received the tenencias of Medinaceli in 1146. That year Alfonso sent him, Ponce Giraldo de Cabrera, Ermengol VI of Urgell, and Martín Fernández de Hita to help the king's Muslim ally Sayf al-Dawla regain the cities of Baeza, Jaén and Úbeda. This they succeeded in doing, but they soon quarrelled with Sayf and fighting ensued, during which Sayf was defeated and his submission to Alfonso reenforced. In January 1147 Manrique played a key rôle in the capture of Calatrava, a fact the king acknowledged in a charter drawn up on 9 January. In August Manrique took part in the reconquest of Almería and its hinterland, which included the taking of Baeza, which he immediately received from the king as a tenencia. He is highly praised by the anonymous author of the Poema de Almería, who cites his splendour and generosity ahead of his wisdom and valour:

Count Manrique, a sincere friend of Christ, valiant in warfare, is placed in charge of all these towns [And%C3%BAjar, Baños, Bayona and Baeza]. He was liked by all, just as he was liked by the Emperor, so that he shone among the Saracens and Christians alike. Illustrious in reputation and beloved by all, bountiful and generous, he was niggardly to no man. He was skilled in arms, he possessed the mind of a sage, he delighted in battle and was a master of the science of war.

This emphasis was typical in the period, when generosity, munificence and prodigality were considered signs of greatness, and the rewarding of followers was essential to maintaining one's power. In Baeza, Manrique's rule can be traced for a decade, until 1157. In 1148 he received the tenencia of Segovia. In November 1148 Manrique and others of his famiy donated some houses in Toledo, which he ruled at the time, to Gonzalo de Marañón. It is a sign of the diversity of his interests that he owned urban properties in the most important city in the kingdom.

In 1149 Manrique was entrusted with the tutorship of the king's eldest son and heir, the future Sancho III, who was raised in his household. Some indication of the size of Manrique's household—court is perhaps the better word—is given by the fact that he employed at least two individuals, Gonzalo Peláez and García Díaz, in the post of alférez in 1153 and 1156 respectively. Manrique is also known to have a employed a chaplain (capellanus). In 1153 this office was filled by a certain Sebastian, who was also acting as Manrique's scribe when needed. By November 1155 he had hired a clerk named Sancho who signed his documents as "chancellor".

In February 1152 Manrique encouraged the settlement of Balaguera and Cedillo in the Extremadura by dividing his property there amongst some settlers. Sometime before December 1153, Manrique married Ermessinde, daughter of Aimeric II of Narbonne and a cousin of Raymond Berengar IV of Barcelona. She bore him eight children, four sons and four daughters: Aimerico, Ermengarda, Guillermo (William), Manrique, María, Mayor (Amilia), Pedro, Sancha and Elvira. Three of his daughters married among the highest nobility: María married Diego López II de Haro, Mayor to Gómez González de Manzanedo, and Elvira to Ermengol VIII of Urgell, grandson of Ermengol VI, Manrique's fellow envoy of 1146 and the husband of his cousin Elvira Rodríguez.[16] On 5 December 1153, in their first recorded action as husband and wife, Manrique and Ermessinde gave the village of Cobeta to the Benedictine monasteries of Arlanza, San Salvador de Oña and Santo Domingo de Silos, and the cathedral of Santa María in Sigüenza, at the time under construction according to a Benedictine plan. The charter of this donation was drawn up by Sebastian. It survives with tags which once attached a seal, now lost. Manrique may have been the first member of the Castilian nobility to employ a seal to authenticate documents. The royal chancery had only been employing them from 1146, though episcopal chanceries had already adopted them under French influence (1140). Manrique's marital connexion with the rulers of Narbonne may have influenced his decision, and his seal was probably based on the type used in Languedoc at the time. In 1163, when the chancery of the young Alfonso VIII adopted a seal, it was probably based on Manrique's. The earliest surviving aristocratic seal from Castile is one of Manrique's son Pedro, from document of 1179 drawn up at Calatayud. A look at the earliest seals of Alfonso VIII and Pedro Manrique suggests that Manrique's own seal showed an armed, stylised, equestrian figure patterned after Anglo-French designs, but left-facing in the Mediterranean fashion.

On 21 April 1154 Manrique and Ermessinde issued a sweeping fuero to the town of Molina de Aragón. The document survives only in a thirteenth-century copy, and it may have been amended in light of later twelfth-century fueros, although much of its material has precedents in the early twelfth century. It lists the privileges of the inhabitants, the rents owed to Manrique, a list of officials who would serve on the municipal council and an extensive legal code. A large portion of the law deals with the formation of the local militia. Knights (caballeros) who lived in the town with their families for a certain period of the year were exempted from taxes. A fifth of the booty taken by the local militia in war was to go to Manrique, and those who skipped out on their military obligations were fined. Unprecedentedly (and perhaps suspiciously), a maintenance was paid to those who captured Muslim leaders in battle and had to temporarily support them before they were handed over to the king. The fuero also mandated watchtower duty, a medical allowance for wounds received in war, the use of battle standards, and standards of military equipment for both cavalry and infantry. Also without precedent is a law requiring all those with a certain amount of wealth to purchase a horse and serve in the militia as a knight. If the thirteenth-century copy is accurate to the original, the fuero of Molina marks a transition in the customary law martial law of the peninsula, especially of Castile and Aragon. The semi-independent nature of the rule of Manrique and his successors at Molina has been likened to the rule of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar at Valencia two generations earlier and to the contemporary rule of Pedro Ruiz de Azagra in Albarracín. Manrique even used the formula Dei gratia comes ("count by the grace of God"), implying that his power did not derive from the king.

When the lordship passed to the crown through the marriage of María de Molina and Sancho IV, Molina was retained as a subsidiary title until the time of Isabel II.

In November 1155 Manrique bought the villa of Alcolea from García Garcés de Aza for 1,000 maravedís, a sign of his wealth. It is a sign of his power influence that in 1156 he, as governor (tenente) of Baeza and its entire district, was, under exceptional circumstances, conceded by the king the right to make three grants of reconquered (and thus royal) land to his supporters in the region, as part of the programme of repopulation. The charters, which did not require the confirmation of any members of the royal court, were drawn up by Manrique's scribe and authenticated with Manrique's seal. It is probable that the exceptional circumstances which led Alfonso to leave the function of the royal chancery in the hands of Manrique and his household staff was the pressing need to secure the region against the the threatening Almohads.

That same year (1156), Manrique was entrusted with the tenencia of Burgo de Osma, which he subinfeudated to his vassal Diego Pérez as alcalde. Manrique was also governing the Mediterranean port city of Almería (near Alcolea) in January 1157. Later that year both Almería and Baeza were lost to the Almohads. In August that year, Alfonso VII died. According to the De rebus Hispaniae, written by a Navarrese cleric, Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada, a century later, the division of Alfonso VII's empire between his heirs was a result of the evil counsel of Manrique Pérez de Lara and Fernando Pérez de Traba (possibly Manrique's maternal uncle), who together "aimed to sow the seed of discord". Alfonso's elder son, Sancho, succeeded in Castile and Toledo, while his second son, Ferdinand II, succeeded in León and Galicia. Sancho died on 31 August 1158 and Manrique became regent and guardian of the child king Alfonso VIII. At least one later account with a pro-Leonese bias, the Chronicon mundi of Lucas de Tuy, asserts that Ferdinand II became regent and protector of Alfonso VIII, but this is a fabrication.

In the dispute over Alfonso VIII's regency that followed Sancho's death, the Lara family forced the Castro family into exile, igniting a civil war. Rodrigo Jiménez, perhaps relying on a popular legend, states that Manrique had the body of Gutierre Fernández de Castro disinterred and held as a ransom. In January 1160 he took over the government of the Extremadura on behalf of the crown, all the while continuing to hold Atienza and Toledo. In March 1160 the exiled Castro leader, Fernando Rodríguez, returned to confront the Laras and their allies in the Battle of Lobregal. The Castros were victorious, and Manrique's brother Nuño was captured, but the Laras were not displaced. By March 1161 the guardianship of the young Alfonso, initially held by Gutierre Fernández, followed by García Garcés de Aza, was being exercised by Manrique, who styled himself nutritius regis ("nurturer of the king"). In 1162 Manrique lost the tenencias of Atienza and Toledo and was placed in San Esteban de Gormaz.

Manrique was killed by Fernando Rodríguez at the Battle of Huete, a repeat of the disaster of Lobregal, in 1164, but the day of this battle is uncertain. The Anales toledanos primeros date it to 9 July and note Manrique's death: "They killed Count Manrique on the ninth day of the month of July in the Era 1202 [AD 1164]." There is a charter dated 21 June 1164, an earlier source than the Anales, that places the battle on 3 June:

. . .in the year this charter was written when Fernando Rodríguez with those of Toledo and of Huete fought with the count Don Manrique and this same count Don Manrique was killed, and many other Castilians [with him]. . . This charter was made on the fifth day of the week, the eleventh kalends of July [Thursday, 21 June]. Under the Era 1202 [AD 1164]. Fifteen and three days before this charter was made [3 June] Count Don Manrique and his knights were killed.

Manrique was buried in the Cistercian abbey of Santa María de Huerta, founded by Alfonso VII in 1147 and destined to be heavily patronised by the Lara family. His widow, Ermessinde, was still alive as late as 1175, when she donated property in Molina de Aragón to her grandson García Pérez and to the Order of Calatrava. She also made many donations to Santa María de Huerta and to the Praemonstratensian monastery of Santa María de La Vid. Besides Calatrava, she patronised the Knights Hospitaller. She founded a Praemonstratensian convent at Brazacorta.

Notes

^ Barton, 264–65, provides an overview of Manrique's immediate family, public career and important private acts with documentary source citations and a brief bibliography.

^ Prose translation in Barton and Fletcher, 261. Their verse numbering differs from that Lipskey, 176, The Poem of Almería, vv. 315–19, whose translation is reproduced here for comparison:

He [Pedro] governed his own land for many years. His son followed in the steps of his father. For this reason he was enriched with honor in the flower of his youth and respected by the Emperor [Alfonso VII]. It was his rule to be witness to the law and to be an evil plague to the Moors.

^ Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, 102, who spells Manrique's name in Spanish Amalrico or Malric.

^ Barton, 229 n2.

^ Some authors consider Manrique the eldest son, but Barton, 264 and 305, places Manrique second after Álvaro.

^ According to one historian he received Ávila in 1133, but the documentary sources to do not support this conclusion, Barton, 264 n10.

^ Barton, 264 n4: Amalricus ipso die quo hec carta facta fuit factus comes.

^ Chronica Adefonsi imperatoris, II, §191, in Lipskey 154–55.

^ Barton, 175.

^ His rule in Baeza had begun by 18 August, cf. Barton, 151 n13.

^ Prose translation in Barton and Fletcher, 261. Their verse numbering differs from that Lipskey, 176, The Poem of Almería, vv. 305–14, whose translation is reproduced here for comparison:

Count Manrique de Lara is made governor of these cities. He is a celebrated warrior and a true friend of Christ. He is pleasing to all including the Emperor, so that he stands out among the Moors and the Christians. Illustrious in his fame, he is loved by all. Splendid and generous, he was mean with no one. He was distinguished in the art of war, and he had the mind of a sage. He rejoiced in battle and possessed a great knowledge of military affairs. He imitated his father, Count Pedro de Lara, in all that he did.

^ Barton, 91.

^ This charge can be dated from 1 March that year, cf. Barton, 264 n6.

^ Barton, 59.

^ This act appears, edited, in its original Latin, in Barton, 313–14.

^ Barton, 305; Duggan, 93–95; Doubleday, 157.

^ Barton names Silos on p. 264, but San Pedro de Cardeña on p. 60.

^ Barton, 60–61. It is possible, though unlikely, that the seal was a later addition and did not emanate from Manrique's chancery.

^ Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, 103.

^ Barton, 60–61.

^ Fletcher, 98 and 106 n92.

^ Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, 101–119.

^ For the date, cf. Barton, 265 n27.

^ Barton, 102.

^ Powers, 36.

^ Duggan, 94, citing Luis Salazar y Castro.

^ Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, 101–02.

^ The charter of this transaction was drawn up at Ayllón by Sancho (Sancius cancellarius comite Almarich). Sancho was still working for Manrique the next year (1156), cf. Barton, 60.

^ The documents are edited in Sánchez Belda, 58–61.

^ Sánchez Belda, 47–57.

^ Barton, 92.

^ Doubleday, 35.

^ Barton, 18–19. There is evidence that the division was planned as early as 1143, two years before Manrique was raised to the rank of count.

^ a b Dyer, 150–51.

^ Barton, 154.

^ Barton, 264 n7.

^ In Flórez, 391: Mataron al Conde Manrich en IX. dias del mes de Julio Era MCCII.

^ Quoted in Barton, 264 n1: . . .in illo anno fuit ista carta scripta quando Fernando Rodriz con los de Toleto et de Uepte lidio con el comite don Marric et fuit mortuus ibi el comite don Marric, et alios castellanos multos. . . Facta carta notu die Va feria XI kalendas iulii. Sub Era MCCII. Quindecim et tres dies antea fuit ista carta facta quam mortuus fuisset Comite don Marric et suos milites.

^ Barton, 201.

ERMESINDE de Narbonne, daughter of AIMERY [II] Vicomte de Narbonne & his wife Ermesinde --- (-7 Jan 1177, bur Santa María de Huerta). “Ermessenda comitissa…quondam uxor Almarrici comitis…cum filiis meis…domno Amelrico et domno Petro atque Guillelmo et domna Maria et domna Sancia et domna Ermengard” donated property to Burgos cathedral by charter dated 14 Aug 1164[1029]. “Armesen comitissa, uxor comitis Almarrich et filia Aimerich de Narbonna” donated property “Arandilla” to the monastery of Huerta by charter dated 14 Mar 1167[1030]. Manrique & his wife had [seven] children:

a) don MANRIQUE Manrique (-1178). “Ermessenda comitissa…quondam uxor Almarrici comitis…cum filiis meis…domno Amelrico et domno Petro atque Guillelmo et domna Maria et domna Sancia et domna Ermengard” donated property to Burgos cathedral by charter dated 14 Aug 1164[1031]. Vicomte de Narbonne. “Almaricus dux Narbone…fratrem suum comitem Petrum” donated property “la mitad de las salinas de Terceguela” to the monastery of Huerta by charter dated 17 May 1172[1032].

b) don PEDRO Manríque de Lara (-Jan 1202, bur Santa María de Huerta). “Ermessenda comitissa…quondam uxor Almarrici comitis…cum filiis meis…domno Amelrico et domno Petro atque Guillelmo et domna Maria et domna Sancia et domna Ermengard” donated property to Burgos cathedral by charter dated 14 Aug 1164[1033]. Conde before 1164. Señor de Molina y Mesa. “Almaricus dux Narbone…fratrem suum comitem Petrum” donated property “la mitad de las salinas de Terceguela” to the monastery of Huerta by charter dated 17 May 1172[1034]. Mayordomo mayor of Fernando II King of Leon 11 Feb 1185. The Anales Toledanos record the death in Jan 1202 of “el Conde D. Pedro”[1035]. m firstly ([1170/73]%29 as her second husband, Infanta doña SANCHA de Navarra, widow of GASTON [V] Vicomte de Béarn, daughter of GARCIA VI "el Restaurador" King of Navarre & his second wife doña Urraca Alfonso “la Asturiana” de Castilla (1148-1176). m secondly MARGUERITE [consanguinea of HENRY II King of England[1036 (-after 17 Nov 1189). m thirdly (after 1195) as her second husband, doña MAFALDA, widow of don PEDRO Ruiz de Guzmán, daughter of ---. Pedro & his first wife had [three] children:

i) don GARCÍA Pérez (-after 3 Mar 1183).

ii) [do%C3%B1a ELVIRA Pérez (-1220). “Comitissa Gelovira Petri…cum viro meo domno Armengaudo” donated property to León cathedral by charter dated 1182[1037]. Her parentage is also suggested by the charter dated 1228 under which her daughter Aurembiax granted property to “Nuño Pérez fijo del conde don Pedro, mio cormano”[1038]. Although “cormano/congermano” is more often interpreted as cousin, under the suggested reconstruction shown here Nuño Pérez would have been Aurembiax´s maternal uncle, although born from her maternal grandfather´s third marriage and so born around the same time as Aurembiax herself. Canal Sánchez-Pagín suggests that Elvira, wife of Armengol [VIII], was the daughter of Conde Pedro Alfonso (of the Vela family, see Chapter 25.B below)[1039]. However, Pedro Alfonso´s daughter Elvira is named in her mother´s 1156 testament and was probably born considerably earlier if her parents´ marriage is correctly dated to [1130]. She is therefore unlikely to have been the same person as the wife of Armengol [VIII], whose daughter´s birth is dated towards the end of the 12th century. Sánchez de Mora suggests a possible explanation for all these apparent inconsistencies: Armengol [VIII] married twice, firstly “Elvira Pérez” (although Sánchez de Mora appears to accept that she was the daughter of Conde Pedro Alfonso), secondly “Elvira Núñez” who would have been the mother of Aurembiax and who Sánchez de Mora suggests could have been the daughter of Nuño Pérez de Lara (see below). This would mean that “cormano” could be given its usual interpretation in the 1228 charter of Aurembiax, who would have belonged to the same generation as the beneficiary of that document. It would also explain another document, dated 20 Apr 1228, under which Aurembiax granted property to “Fernando Álvarez, mio cormano, filio del conde don Alvaro”[1040]. In addition, the dating of the birth of Aurembiax herself to [1196] is difficult to understand if she was the daughter of Elvira Pérez, married to her father already in 1182, but would be natural if she was the daughter of a second marriage. It is recognised that, if Elvira Pérez was the daughter of Conde Pedro Manrique as suggested here, she would only have been about 12 years old at the time of the 1182 charter, presumably recently married, which suggests that this may not be a perfect fit for her parentage. In conclusion, there appears to remain considerable uncertainty about the identity of the wife of Armengol [VIII] Conde de Urgel. Elvira gave possession of Urgel to Pedro II King of Aragon in 1209, on the death of her first husband without male heirs, in return for the king’s protection of her daughter’s rights. The primary source which confirms her second marriage has not yet been identified. Her second husband defended his step-daughter’s rights to Urgel before Jaime I King of Aragon in 1228. m firstly ([1178]%29 ARMENGOL [VIII] de Urgel, son of ARMENGOL [VII] "él de Valencia" Conde de Urgel & his wife Dulce de Foix ([1158]-1209). He succeeded his father in 1184 as Conde de Urgel. m secondly don GUILLEM de Cervera, son of --- (-after 1228).]

iii) don MANRIQUE Pérez (-Feb 1239). He succeeded as Vicomte de Narbonne.

- VICOMTES DE NARBONNE.

Pedro & his third wife had [three] children:

iv) don GONZALO Pérez de Lara . 3rd Señor de Molina y Mesa. m doña SANCHA Gómez de Traba, daughter of don GÓMEZ Gónzalez de Traba & his [first/second] wife ---. Gonzalo & his wife had one child:

(a) doña MAFALDA González de Lara (-[before Sep 1244]). Señora de Molina y Mesa. m (1240) as his first wife, Infante don ALFONSO de León Señor de Soria, son of don ALFONSO IX King of León & his second wife Infanta doña Berenguela de Castilla (Autumn 1202-Salamanca 6 Jan 1272, bur Ciudad Real, castle of Calatrava-la-Nueva). Señor de Molina y Mesa in 1240, by right of his wife.

v) don RODRIGO Pérez . His brother Aimery Vicomte de Narbonne granted him Montpesat and Lac, in Narbonne, in 1208[1041].

vi) [don NUÑO Pérez (-after 1228). His parentage is suggested by the charter dated 1228 under which Aurembiax Condesa de Urgel granted property to “Nuño Pérez fijo del conde don Pedro, mio cormano”[1042]. Although “cormano/congermano” is more often interpreted as cousin, under the suggested reconstruction shown here Nuño Pérez would have been Aurembiax´s maternal uncle, although born from her maternal grandfather´s third marriage and so born around the same time as Aurembiax herself.]

c) don GUILLERMO Manrique de Lara (-after 14 Aug 1164). “Ermessenda comitissa…quondam uxor Almarrici comitis…cum filiis meis…domno Amelrico et domno Petro atque Guillelmo et domna Maria et domna Sancia et domna Ermengard” donated property to Burgos cathedral by charter dated 14 Aug 1164[1043].

d) doña MARÍA Manrique . “Ermessenda comitissa…quondam uxor Almarrici comitis…cum filiis meis…domno Amelrico et domno Petro atque Guillelmo et domna Maria et domna Sancia et domna Ermengard” donated property to Burgos cathedral by charter dated 14 Aug 1164[1044]. The mid-14th Century Nobiliario of don Pedro de Portugal Conde de Barcelós records that “Diego Lopez el bueno” married “doña Maria Manriquez, hija del conde don Manrique de Lara”, adding that she left him “con un herrero de Burgos”[1045]. m (befote 1190, divorced 1192) as his first wife, don DIEGO López "el Bueno", Conde de Haro Señor Soberano de Vizcaya, son of don LOPE Díaz Conde de Haro, Señor Soberano de Vizcaya & his second wife doña Aldonza Rodríguez (-Burgos 16 Sep 1214).

e) 1046]doña MAYOR [Amilia] Manrique (-after 27 May 1182). Barton suggests that the wife of Gómez González was doña Mayor [Amilia] Manrique, daughter of conde don Manrique Pérez & his wife Ermesinde Ctss de Narbonne, who confirmed a grant of property by her supposed sister doña María Manrique to the see of Burgos 27 May 1182[1047]. However, it is likely that this refers to the same person as Gómez´s wife named Milia. Barton´s source has not yet been consulted directly, but it is possible that it does not explicitly refer to the relationship between the grantor and Mayor. The absence of a daughter named Mayor from the charter of her supposed mother dated 14 Aug 1164 also suggests that this affiliation may not be correct. m don GÓMEZ González de Manzanedo, son of conde don GONZALO Rodríguez de Bureba & his first wife [do%C3%B1a Estefanía López] (-12 Oct 1182).]

f) doña SANCHA Manrique (-after 14 Aug 1164). “Ermessenda comitissa…quondam uxor Almarrici comitis…cum filiis meis…domno Amelrico et domno Petro atque Guillelmo et domna Maria et domna Sancia et domna Ermengard” donated property to Burgos cathedral by charter dated 14 Aug 1164[1048].

g) doña ERMENGARDA Manrique . “Ermessenda comitissa…quondam uxor Almarrici comitis…cum filiis meis…domno Amelrico et domno Petro atque Guillelmo et domna Maria et domna Sancia et domna Ermengard” donated property to Burgos cathedral by charter dated 14 Aug 1164[1049]. Vicomtesse de Narbonne.

El Conde don Manrique de Lara fue Señor de Molina, y cafô cõ doña Ermefenda hija de don Aymerique Señor de Narbona deudos de la Cafa Real de Francia, que fue vaffallo del Emperador don Alonfo Rey de Caftilla octavo defte nombre, y fu Alferez mayor, y Rico hombre, y cõfirmador de fus Previlegios, como fe lle en Eftevan de Garivay en el año de 1134 onde fe firma Don Almerico Alferez del Rey. Tuvo en ella a don Pedro Manrique de Lara Señor de Molina, y a doña Mofalda Manrique Reyna de Portugal muger de don Alonfo Enriquez primero Rey de Portugal, y a doña Maria Manrique, que cafô con don Diego Lopez de Haro el bueno Señor de Vizcaya, como fe refirio en el cap. 45 defta hiftoria. La forma como el Conde dõ Manrique vuo el Señorio de Molina, efcrive el Conde don Pedro en el titulo 10 diziendo afsi. El Rey de Caftilla, y el Rey de Aragon avian contienda fobre el Señorio de Molina, que vno dezia q era fuya, y el otro tambien. El Conde don Manrique era vafallo del Rey de Caftilla; y fu natural, y era compadre del Rey de Aragon, y mucho fu amigo. Y viendo la contienda que entre ellos avia, pidioles que dexaffen efte pleyto en fus manos, q el les daria fentencia acontento de ambos, que fueffe buena y fundada por derecho. Y los Reyes fueron contentos defto, y dieronle fus cartas, en que dexavan aquel pleyto en fus manos. Y defpues que vuo en fi efte compromiffo, dio por fentencia, que revocava, y dava por ninguno qualquiere derecho, que los Reyes de Caftilla y Aragon tuvieffen en Molina, y que lo ponia todo en fi, y que de alli adelante quedaffe Molina para el y fus decendientes en Mayoradgo. Y los Reyes holgaron dello, y otorgaron la fentencia, que dio el Conde. NOBLEZA DEL ANDALVZIA Por Gonçalo Argote de Molina, Sevilla 1588. Del Origen y Principio de la Cafa de Lara, y de fus Armas. Cap. LXII. Pág. 56

| 1110 |

1110

|

||

| 1140 |

1140

|

||

| 1164 |

July 9, 1164

Age 54

|

El Valle de Altomira, Province of Cuenca, Castille La Mancha, Spain

|

|

| ???? | |||

| ???? | |||

| ???? | |||

| ???? |

Cistercian abbey of Santa María de Huerta, Huerta, CL, Spain

|