Please add profiles for those who were born, lived or died in Charleston City or County, South Carolina.

History of Charleston

Charleston was founded in 1670 as Charles Town, honoring King Charles II of England. Its initial location at Albemarle Point on the west bank of the Ashley River (now Charles Towne Landing) was abandoned in 1680 for its present site, which became the fifth-largest city in North America within ten years. One of the key cities in the British colonization of the Americas, Charles Town played a major role in the slave trade, which laid the foundation for the city's size and wealth, and was dominated by a slavocracy of plantation owners and slave traders. Independent Charleston slave traders like Joseph Wragg were the first to break through the monopoly of the Royal African Company, pioneering the large-scale slave trade of the 18th century. Historians estimate that "nearly half of all Africans brought to America arrived in Charleston", most at Gadsden's Wharf. Despite its size, it remained unincorporated throughout the colonial period; its government was handled directly by a colonial legislature and a governor sent by London, England. Election districts were organized according to Anglican parishes, and some social services were managed by Anglican wardens and vestries. Charleston adopted its present spelling with its incorporation as a city in 1783 at the close of the Revolutionary War. Population growth in the interior of South Carolina influenced the removal of the state government to Columbia in 1788, but the port city remained among the ten largest cities in the United States through the 1840 census. The only major antebellum American city to have a majority-enslaved population, Charleston was controlled by an oligarchy of white planters and merchants who successfully forced the federal government to revise its 1828 and 1832 tariffs during the Nullification Crisis and launched the Civil War in 1861 by seizing the Arsenal, Castle Pinckney, and Fort Sumter from their federal garrisons. In 2018, the city formally apologized for its role in the American Slave trade after CNN noted that slavery "riddles the history" of Charleston.

As part of the Southern theater of the American Revolution, the British attacked the town in force three times. The loyalty of the white southerners had largely been forfeited, however, by British legal cases (such as the 1772 Somerset case which marked the prohibition of slavery in England and Wales; a significant milestone in the Abolitionist struggle) and military tactics (such as Dunmore's Proclamation in 1775) that promised the emancipation of the planter's slaves; these efforts did however, unsurprisingly win the allegiance of thousands of Black Loyalists.

The Battle of Sullivan's Island saw the British fail to capture a partially constructed palmetto palisade from Col. Moultrie's militia regiment on June 28, 1776. The Liberty Flag used by Moultrie's men formed the basis of the later South Carolina flag, and the victory's anniversary continues to be commemorated as Carolina Day.

Making the capture of Charlestown their chief priority, the British sent Gen. Clinton, who began his siege of Charleston on April 1, 1780, with about 14,000 troops and 90 ships. Bombardment began on March 11. The rebels, led by Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, had about 5,500 men and inadequate fortifications to repel the forces against them. After the British cut his supply lines and lines of retreat at the battles of Monck's Corner and Lenud's Ferry, Lincoln's surrender on May 12 became the greatest American defeat of the war.

The British continued to hold Charlestown for over a year following their defeat at Yorktown in 1781, although they alienated local elites by refusing to restore full civil government. General Nathanael Greene had entered the state after Cornwallis's pyrrhic victory at Guilford Courthouse and kept the area under a kind of siege. General Alexander Leslie, commanding Charlestown, requested a truce in March 1782 to purchase food for his garrison and the town's inhabitants. Greene refused and formed a brigade under Mordecai Gist to oppose British forays. One such foray in August led to a British victory at the Combahee River, but Charlestown was finally evacuated in December 1782. Gen. Greene presented the leaders of the town with the Moultrie Flag.

From the summer of 1782, French planters fleeing the Haitian Revolution began arriving in the port with their slaves. The major outbreak of yellow fever that occurred in Philadelphia the next year probably spread there from an epidemic these refugees brought to Charleston, although it was not publicly reported at the time. Over the 19th century, the health officials and newspapers of the town came under repeated criticism from Northerners, fellow Southerners, and one another for covering up epidemics as long as possible in order to keep up the city's maritime traffic. The distrust and mortal risk meant that between July and October each year communication nearly shut down between the city and the surrounding countryside, which was less susceptible to yellow fever.

The spelling Charleston was adopted in 1783 as part of the city's formal incorporation.

Although Columbia replaced it as the state capital in 1788, Charleston became even more prosperous as Eli Whitney's 1793 invention of the cotton gin sped the processing of the crop over 50 times. The development made short-staple cotton profitable and opened the upland Piedmont region to slave-based cotton plantations, previously restricted to the Sea Islands and Lowcountry. Britain's Industrial Revolution—initially built upon its textile industry—took up the extra production ravenously and cotton became Charleston's major export commodity in the 19th century. The Bank of South Carolina, the second-oldest building in the nation to be constructed as a bank, was established in 1798. Branches of the First and Second Bank of the United States were also located in Charleston in 1800 and 1817.

Throughout the Antebellum Period, Charleston continued to be the only major American city with a majority-slave population. The city's widespread use of slaves as workers was a frequent subject of writers and visitors: a merchant from Liverpool noted in 1834 that "almost all the working population are Negroes, all the servants, the carmen & porters, all the people who see at the stalls in Market, and most of the Journeymen in trades". American traders had been prohibited from equipping the Atlantic slave trade in 1794 and all importation of slaves was banned in 1808, but American ships long refused to permit British inspection, and smuggling remained common. Much more important was the domestic slave trade, which boomed as the Deep South was developed in new cotton plantations. As a result of the trade, there was a forced migration of more than one million slaves from the Upper South to the Lower South in the antebellum years. During the early 19th century, the first dedicated slave markets were founded in Charleston, mostly near Chalmers & State streets. Many domestic slavers used Charleston as a port in what was called the coastwise trade, traveling to such ports as Mobile and New Orleans.

Slave ownership was the primary marker of class and even the town's freedmen and free people of color typically kept slaves if they had the wealth to do so. Visitors commonly remarked on the sheer number of blacks in Charleston and their seeming freedom of movement, though in fact—mindful of the Stono Rebellion and the violent slave revolution that established Haiti—the whites closely regulated the behavior of both slaves and free people of color. Wages and hiring practices were fixed, identifying badges were sometimes required, and even work songs were sometimes censored. Punishment was handled out of sight by the city's Work House, whose fees provided the municipal government with thousands a year. In 1820, a state law mandated that each act of manumission (freeing a slave) required legislative approval, effectively halting the practice.

The effects of slavery were pronounced on white society as well. The high cost of 19th-century slaves and their high rate of return combined to institute an oligarchic society controlled by about ninety interrelated families, where 4% of the free population controlled half of the wealth, and the lower half of the free population—unable to compete with owned or rented slaves—held no wealth at all. The white middle class was minimal: Charlestonians generally disparaged hard work as the lot of slaves. All the slaveholders taken together held 82% of the city's wealth and almost all non-slaveholders were poor. Olmsted considered their civic elections "entirely contests of money and personal influence" and the oligarchs dominated civic planning: the lack of public parks and amenities was noted, as was the abundance of private gardens in the wealthy's walled estates.

In the 1810s, the town's churches intensified their discrimination against their black parishioners, culminating in Bethel Methodist's 1817 construction of a hearse house over its black burial ground. 4,376 black Methodists joined Morris Brown in establishing Hampstead Church, the African Methodist Episcopal church now known as Mother Emanuel. State and city laws prohibited black literacy, limited black worship to daylight hours, and required a majority of any church's parishioners be white. In June 1818, 140 black church members at Hampstead Church were arrested and eight of its leaders given fines and ten lashes; police raided the church again in 1820 and leaned on it in 1821.

In 1822, members of the church, led by Denmark Vesey, a lay preacher and carpenter who had bought his freedom after winning a lottery, planned an uprising and escape to Haiti—initially for Bastille Day—that failed when one slave revealed the plot to his master. Over the next month, the city's intendant (mayor) James Hamilton Jr. organized a militia for regular patrols, initiated a secret and extrajudicial tribunal to investigate, and hanged 35 and exiled 35 or 37 slaves to Spanish Cuba for their involvement. In a sign of Charleston's antipathy to abolitionists, a white co-conspirator pled for leniency from the court on the grounds that his involvement had been motivated only by greed and not by any sympathy with the slaves' cause. Governor Thomas Bennett Jr. had pressed for more compassionate and Christian treatment of slaves but his own had been found involved Vesey's planned uprising. Hamilton was able to successfully campaign for more restrictions on both free and enslaved blacks: South Carolina required free black sailors to be imprisoned while their ships were in Charleston Harbor though international treaties eventually required the United States to quash the practice; free blacks were banned from returning to the state if they left for any reason; slaves were given a 9:15 pm curfew; the city razed Hampstead Church to the ground and erected a new arsenal. This structure later was the basis of the Citadel's first campus. The AME congregation built a new church but in 1834 the city banned it and all black worship services, following Nat Turner's 1831 rebellion in Virginia.

In 1832, South Carolina passed an ordinance of nullification, a procedure by which a state could, in effect, repeal a federal law; it was directed against the most recent tariff acts. Soon, federal soldiers were dispensed to Charleston's forts, and five United States Coast Guard cutters were detached to Charleston Harbor "to take possession of any vessel arriving from a foreign port, and defend her against any attempt to dispossess the Customs Officers of her custody until all the requirements of law have been complied with." This federal action became known as the Charleston incident. The state's politicians worked on a compromise law in Washington to gradually reduce the tariffs.

On 27 April 1838, a massive fire broke out around 9:00 in the evening. It raged until noon the next day, damaging over 1,000 buildings, a loss estimated at $3 million at the time. In efforts to put the fire out, all the water in the city pumps was used up. The fire ruined businesses, several churches, a new theater, and the entire market except for the fish section. Most famously, Charleston's Trinity Church was burned. Another important building that fell victim was the new hotel that had been recently built. Many houses were burnt to the ground. The damaged buildings amounted to about one-fourth of all the businesses in the main part of the city. The fire rendered penniless many who were wealthy. Several prominent store owners died attempting to save their establishments. When the many homes and business were rebuilt or repaired, a great cultural awakening occurred. In many ways, the fire helped put Charleston on the map as a great cultural and architectural center. Previous to the fire, only a few homes were styled as Greek Revival; many residents decided to construct new buildings in that style after the conflagration. This tradition continued and made Charleston one of the foremost places to view Greek Revival architecture. The Gothic Revival also made a significant appearance in the construction of many churches after the fire that exhibited picturesque forms and reminders of devout European religion.

By 1840, the Market Hall and Sheds, where fresh meat and produce were brought daily, became a hub of commercial activity. The slave trade also depended on the port of Charleston, where ships could be unloaded and the slaves bought and sold. The legal importation of African slaves had ended in 1808, although smuggling was significant. However, the domestic trade was booming. More than one million slaves were transported from the Upper South to the Deep South in the antebellum years, as cotton plantations were widely developed through what became known as the Black Belt. Many slaves were transported in the coastwise slave trade, with slave ships stopping at ports such as Charleston.

Charleston played a major part in the Civil War. As a pivotal city, both the Union and Confederate Armies vied for power over the Holy City. It is no surprise that the war ended only mere months after the Union forces took control of Charleston. Not only did the Civil War end not long after Charleston's surrender, but the Civil War began here as well.

Following the election of Abraham Lincoln, the South Carolina General Assembly voted on December 20, 1860, to secede from the Union. South Carolina was the first state to secede. On December 27, Castle Pinckney was surrendered by its garrison to the state militia and, on January 9, 1861, Citadel cadets opened fire on the USS Star of the West as it entered Charleston Harbor.

The first full battle of the American Civil War occurred on April 12, 1861, when shore batteries under the command of General Beauregard opened fire on the US Army-held Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. After a 34-hour bombardment, Major Robert Anderson surrendered the fort.

On December 11, 1861, an enormous fire burned over 500 acres of the city.

Union control of the sea permitted the repeated bombardment of the city, causing vast damage. Although Admiral Du Pont's naval assault on the town's forts in April 1863 failed, the Union navy's blockade shut down most commercial traffic. Over the course of the war, some blockade runners got through but not a single one made it into or out of the Charleston Harbor between August 1863 and March 1864. The early submarine H.L. Hunley made a night attack on the USS Housatonic on February 17, 1864.

General Gillmore's land assault in July 1864 was unsuccessful but the fall of Columbia and advance of General William T. Sherman's army through the state prompted the Confederates to evacuate the town on February 17, 1865, burning the public buildings, cotton warehouses, and other sources of supply before their departure.[28] Union troops moved into the city within the month. The War Department recovered what federal property remained and also confiscated the campus of the Citadel Military Academy and used it as a federal garrison for the next 17 years. The facilities were finally returned to the state and reopened as a military college in 1882 under the direction of Lawrence E. Marichak.

After the defeat of the Confederacy, federal forces remained in Charleston during Reconstruction. The war had shattered the city's prosperity, but the black population surged (from 17,000 in 1860 to over 27,000 in 1880) as freedmen moved from the countryside to the major city. Blacks quickly left the Southern Baptist Church and resumed open meetings of the African Methodist Episcopal and AME Zion churches. They purchased dogs, guns, liquor, and better clothes—all previously banned—and ceased yielding the sidewalks to whites. Despite the efforts of the state legislature to halt manumissions, Charleston had already had a large class of free people of color as well. Many were educated and practiced skilled crafts; they quickly became leaders of South Carolina's Republican Party and its legislators. Men who had been free people of color before the war comprised 26% of those elected to state and federal office in South Carolina from 1868 to 1876.

By the late 1870s, industry was bringing the city and its inhabitants back to a renewed vitality; new jobs attracted new residents. As the city's commerce improved, residents worked to restore or create community institutions. In 1865, the Avery Normal Institute was established by the American Missionary Association as the first free secondary school for Charleston's African American population. Gen. Sherman lent his support to the conversion of the United States Arsenal into the Porter Military Academy, an educational facility for former soldiers and boys left orphaned or destitute by the war. Porter Military Academy later joined with Gaud School and is now a university-preparatory school, Porter-Gaud School.

In 1875, blacks made up 57% of the city's and 73% of the county's population. With leadership by members of the antebellum free black community, historian Melinda Meeks Hennessy described the community as "unique" in being able to defend themselves without provoking "massive white retaliation", as occurred in numerous other areas during Reconstruction. In the 1876 election cycle, two major riots between black Republicans and white Democrats occurred in the city, in September and the day after the election in November, as well as a violent incident in Cainhoy at an October joint discussion meeting.

Violent incidents occurred throughout the Piedmont of the state as white insurgents struggled to maintain white supremacy in the face of social changes after the war and granting of citizenship to freedmen by federal constitutional amendments. After former Confederates were allowed to vote again, election campaigns from 1872 on were marked by violent intimidation of blacks and Republicans by conservative Democratic paramilitary groups, known as the Red Shirts. Violent incidents took place in Charleston on King Street in September 6 and in nearby Cainhoy on October 15, both in association with political meetings before the 1876 election. The Red Shirts were instrumental in suppressing the black Republican vote in some areas in 1876 and narrowly electing Wade Hampton as governor, and taking back control of the state legislature. Another riot occurred in Charleston the day after the election, when a prominent Republican leader was mistakenly reported killed.

On August 31, 1886, Charleston was nearly destroyed by an earthquake. The shock was estimated to have a moment magnitude of 7.0 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of X (Extreme). It was felt as far away as Boston to the north, Chicago and Milwaukee to the northwest, as far west as New Orleans, as far south as Cuba, and as far east as Bermuda. It damaged 2,000 buildings in Charleston and caused $6 million worth of damage, at a time when all the city's buildings were valued around $24 million.

Investment in the city continued. The William Enston Home, a planned community for the city's aged and infirm, was built in 1889. An elaborate public building, the United States Post Office and Courthouse, was completed by the federal government in 1896 in the heart of the city. The Democrat-dominated state legislature passed a new constitution in 1895 that disfranchised blacks, effectively excluding them entirely from the political process, a second-class status that was maintained for more than six decades in a state that was majority-black until about 1930.

Charleston languished economically for several decades in the 20th century, though the large federal military presence in the region helped to shore up the city's economy.

The Charleston Hospital Strike of 1969, in which mostly black workers protested discrimination and low wages, was one of the last major events of the civil rights movement. It attracted Ralph Abernathy, Coretta Scott King, Andrew Young, and other prominent figures to march with the local leader, Mary Moultrie.

Joseph P. Riley Jr. was elected mayor in the 1970s, and helped advance several cultural aspects of the city. Riley worked to revive Charleston's economic and cultural heritage. The last 30 years of the 20th century had major new investments in the city, with a number of municipal improvements and a commitment to historic preservation to restore the city's unique fabric. There was an effort to preserve working-class housing of blacks on the historic peninsula, but the neighborhood has gentrified, with rising prices and rents.

The city's commitments to investment were not slowed down by Hurricane Hugo and continue to this day. The eye of Hurricane Hugo came ashore at Charleston Harbor in 1989, and though the worst damage was in nearby McClellanville, three-quarters of the homes in Charleston's historic district sustained damage of varying degrees. The hurricane caused over $2.8 billion in damage. The city was able to rebound fairly quickly after the hurricane and has grown in population.

In 1993, the city was further impacted economically by the end of the Cold War when a decision of the Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC) directed that Naval Base Charleston be closed and that its surface ships and nuclear-powered submarines be relocated to other homeports, primarily Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia and Naval Station Mayport, Florida. Pursuant to BRAC action, Naval Base Charleston was closed on April 1, 1996, although some activities remain under the cognizance of Naval Support Activity Charleston, now part of Joint Base Charleston.

On June 17, 2015, 21-year-old white supremacist Dylann Roof entered the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church and sat in on part of a Bible study before shooting and killing nine people, all blacks. Senior pastor Clementa Pinckney, who also served as a state senator, was among those killed during the attack. The attack garnered national attention, and sparked a debate on historical racism, Confederate symbolism in Southern states, and gun violence, in part based on Roof's online postings. A memorial service on the campus of the College of Charleston was attended by President Barack Obama, Michelle Obama, Vice President Joe Biden, Jill Biden, and Speaker of the House John Boehner.

On June 17, 2018, the Charleston City Council apologized for its role in the slave trade and condemned its "inhumane" history. It also acknowledged wrongs committed against blacks by slavery and Jim Crow laws.

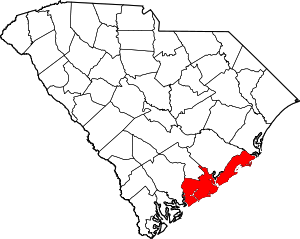

Adjacent Counties

Cities, Towns & Communities other than Charleston City

Links

American Revolution: The Siege of Charleston

Slaveholders & Slaves Surname Matches - 1860 & 1870 Census

Slave Manifests for Charleston, SC