Utinawassis Margaret Grant, Marguerite Ah-Dik Songab Okicheta Bottineau, and Marguerite Ah-Dik Songab Okicheta Bottineau were the matriarchs of The Dakota Nation, The O'Jibway Nation, and The Cree Iron Confederacy as the family of Chief Delonaise Atetaŋkawamduška Wáȟpe Šá and King of the Loons Mamaangĕzide. His stepbrother Red Bear Miscomaquah, Chief Noka Nokay Kadwabida Broken Tooth, and Chief Alexis Bobtail Piche skinned the white men who abused them. A man Charles Chartier once took their money and sold them. Briefly, this incited Chief Kaŋgidaŋ Mdokečiŋhaŋ, Little Crow I to start a war to rescue them. Modern history has ignored the story of the family of the three Starwoman sisters manipulated by greedy European businessmen to obtain access to their trading routes including The NW Trading Company, XY Trading Company, and Hudson Bay Trading Company.

The Leader of The Anishinabewaki Nation of Canada Lake of the Woods.

static.wixstatic.com/media/edc723_929d7d1cb91d4168a00cf345d34864e0~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_568,h_105,al_c,lg_1,q_85,enc_auto/Path%20of%20light.png

upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Anishinaabemowin_map.png

Indigenous descendants of North America view lineage as the foundation of cultural identity.

The family is the central unity of the community, and the wise grandfathers and grandmothers are honored with respect.

Grand Chiefs negotiated Treaties with The United States of America asserting national sovereignty status, established national land boundaries, and established the Supreme Laws of the Land.

A ROYAL NATIVE FAMILY: TWO BROTHERS "Mamaangĕzide and Wáȟpe Šá"

One hundred years before the attack on Ojibwe maple sugar gatherers by Dakota raiders at Sandy Lake, one family’s alliance created a bridge of friendship between eastern Dakota villages and the western Lake Superior Ojibwe.

During this time, intermarriage between members of the Ojibwe and Dakota bands was a common practice that reaffirmed the peaceful commitment between the villages. Around the year 1720, Fox Woman Wabasha (Eshipequag) the daughter of Chief Jos Ojiibway, of the Reindeer Dynasty and Sandy Lake Ojibwe Band Chief Kadawibida No-Ka Gaa-dawaabide Broken Tooth Nooke “Bear” (Ka-ta-wah-be-dah Breshieu) met and married. The marriage unified the paramount leadership families of the Oceti Sakowin of the Dakota and Ojibwe Nations of The Great Lakes. From this union two sons were born, the eldest named Wáȟpe Šá and the younger Mamaangĕzide.

Sadly for the family, the marriage of Wáȟpe Šá’s parents did not last long, as tensions along the indigenous borderlands flared and the alliance between their tribes fell apart, forcing mixed Dakota-Ojibwe households to separate. During these forced separations, “instances were told where the parting between husband and wife was most grieving to behold.” Wáȟpe Šá retained his Oceti Sakowin Dakota heritage and identity and stayed with his father’s village.

Knowing her life would otherwise be in danger, Wáȟpe Šá’s mother left to return to her kin living near Lake Superior at Lake of the Woods.

Together they had a son named Mamaangĕzide, and as he grew he earned a reputation as a leader

of the western Lake Superior Ojibwe. Mamaangĕzide was renowned for his hunting skills, and often extended his hunting expeditions deep into Dakota territory. This was especially dangerous because following the breakup of the Dakota-Ojibwe alliance, renewed tensions in the region saw a drastic increase in violence between the historic rival tribes. The tensions between the Dakota and Ojibwe created a corridor where hunters from both bands avoided going because of the great risk of attack.

In this narrow geographic space, the animal population rebounded and created a rich hunting region. Enticed by the opportunity to find plentiful game, Mamaangĕzide led a small group of “his near relatives, amounting usually to 20 persons, exclusive of children,” and embarked to the hunting grounds “near the borders of the Dakota country, in the midland district lying between the Mississippi and Lake Superior.”

This region was the geographical center of the Indigenous borderlands though Mamaangĕzide had hunted far from his main village before, this time the risk did not pay off. While the small hunting party made preparations for their hunt, Dakota warriors discovered and fired on the party. One of the Ojibwe was wounded in the second volley. The situation appeared desperate to Mamaangĕzide, and he called out in Dakota asking if his halfbrother Wáȟpe Šá was with the Dakota party. The Dakota paused their attack. After a long moment, Wáȟpe Šá stepped out from the tree line to meet with his Ojibwe half-brother, Mamaangĕzide, stopping the fighting between the two parties. The half-brothers shared the same Ojibwe mother, Fox Woman Wabasha (Eshipequag) yet their individual identities stemmed from the community in which they were raised.

Oceti Sakowin Dakota and Anishinabewaki Ojibwe village and kinship structures differed greatly from each other. Each man likely understood the concept of kin and obligation to kin differently, yet their shared maternal connection was strong enough to stop this particular skirmish. An individual’s connection to a large community was one of the keys to survival in the region, but each community was a collection of individual people who had agreed to band together.

The Ojibwe and Dakota differed in how these practices functioned, yet an individual’s need for community was the same for both tribes. While modern identity is made up of a web of affiliations, the nation-state is often the primary lens through which people understand themselves and others. In the Indigenous borderlands, nation-state identity was nonexistent, but that did not mean that there were no firm boundaries of identity that bonded some peoples together while separating others. Family kinship and village ties created these strong bonds and were centers of identity, as well as obligation. On certain occasions, like the meeting of Mamaangĕzide and Wáȟpe Šá, family ties could bridge the gap between cultures.

Mamaangĕzide and Wáȟpe Šá found peace.

Mamaangĕzide daughter Claire Equaywid Ahdik Songab would marry his brother Wáȟpe Šá unifying the nations eternally through the Equaywid-Wáȟpe Šá bloodline, the principal leader of the Oceti Sakowin and Anisishinabe. Claire Equaywid Ahdik Songab and Wáȟpe Šá would become parents of Chief of the Chippewas Pierre Misco Mahqua DeCoteau, Misko-Makwa Red Bear I; Ahdikons; Aceguemanche; Chief Noka Nokay Kadwabida Broken Tooth; Utinawasis "Star Woman" Margaret Son-gabo-ki-che-ta Grant; Angelique Woman LaBatte; Mary Etoukasah-wee Lapoint; Mdewakanton Dakota Chief Wahpehda Red Leaf Wáȟpe šá Wazhazha, II; Mah Je Gwoz Since Ah-dik Songab "Star Woman" and Marie Techomehgood Bottineau, Star Woman.

The brother of Mamaangĕzide and Wáȟpe Šá was called Chief Kaŋgidaŋ “Little Raven” Little Crow I. Chief Kaŋgidaŋ “Little Raven” Little Crow I is the father of Joseph Petit Courbeau III (Aisaince I) Little Shell I, who was the half-brother of Gay Tay Menomin Old Wild Rice (Red Wing I).

In a turn of intermarrying of leadership, Mamaangĕzide's father Chief Kadawibida No-Ka Gaa-dawaabide Broken Tooth Nooke “Bear” (Ka-ta-wah-be-dah Breshieu) was the half-brother of Chief of the Chippewas Pierre Misco Mahqua DeCoteau, Misko-Makwa Red Bear I. Chief of the Chippewas Pierre Misco Mahqua DeCoteau, Misko-Makwa Red Bear I mother was Claire Equaywid Ahdik Songab, the daughter of Mamaangĕzide. Claire Equaywid Ahdik Songab would have relations with Sandy Lake Ojibwe Chief Biauswah II Bayaaswaa "The Dry One" Bajasswa Thomme Qui Faitsecher, the grandfather of Mamaangĕzide. Red Bear I sister, Mah Je Gwoz Since Ah-dik Songab "Star Woman" was the daughter of Wáȟpe Šá and Equaywid. The family intermarrying practices unified a nation, preserved a bloodline, and established a royal native lineage.

In the various diaries, letters, official accounts, travelogues, and histories of this area from the first half of the nineteenth century, there are certain individuals that repeatedly find their way into the story. These include people like the Ojibwe chiefs Buffalo of La Pointe, Flat Mouth of Leech Lake, and the father and son Hole in the Day, whose influence reached beyond their home villages. Fur traders, like Lyman Warren and William Aitken, had jobs that required them to be all over the place, and their role as the gateway into the area for the American authors of many of these works ensure their appearance in them. However, there is one figure whose uncanny ability to show up over and over in the narrative seems completely disproportionate to his actual power or influence. That person is Maangozid (Loon’s Foot) of Fond du Lac.

Naagaanab, a contemporary of Maangozid (Undated, Newberry Library Chicago)

In fairness to Maangozid, he was recognized as a skilled speaker and a leader in the Midewiwin religion. His father was a famous chief at Sandy Lake, but his brothers inherited that role. He married into the family of Zhingob (Shingoop, “Balsam”) a chief at Fond du Lac, and served as his speaker. Zhingob was part of the Marten clan, which had produced many of Fond du Lac’s chiefs over the years (many of whom were called Zhingob or Zhingobiins). Maangozid, a member of the Loon clan born in Sandy Lake, was seen as something of an outsider. After Zhingob’s death in 1835, Maangozid continued to speak for the Fond du Lac band, and many whites assumed he was the chief. However, it was younger men of the Marten clan, Nindibens (who went by his father’s name Zhingob) and Naagaanab, who the people recognized as the leaders of the band.

Certainly some of Maangozid’s ubiquity comes from his role as the outward voice of the Fond du Lac band, but there seems to be more to it than that. He just seems to be one of those people who through cleverness, ambition, and personal charisma, had a knack for always being where the action was. In the bestselling book, The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell talks all about these types of remarkable people, and identifies Paul Revere as the person who filled this role in 1770s Massachusetts. He knew everyone, accumulated information, and had powers of persuasion. We all know people like this. Even in the writings of uptight government officials and missionaries, Maangozid comes across as friendly, hilarious, and most of all, everywhere.

Recently, I read The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely 1833-1849 (U. of Nebraska Press; 2012), edited by Theresa Schenck. There is a great string of journal entries spanning from the Fall of 1836 to the summer of 1837. Maangozid, feeling unappreciated by the other members of the band after losing out to Nindibens in his bid for leadership after the death of Zhingob, declares he’s decided to become a Christian. Over the winter, Maangozid visits Ely regularly, assuring the stern and zealous missionary that he has turned his back on the Midewiwin. The two men have multiple fascinating conversations about Ojibwe and Christian theology, and Ely rejoices in the coming conversion. Despite assurances from other Ojibwe that Maangozid has not abandoned the Midewiwin, and cold treatment from Maangozid’s wife, Ely continues to believe he has a convert. Several times, the missionary finds him participating in the Midewiwin, but Maangozid always assures Ely that he is really a Christian.

J.G. Kohl (Wikimedia Commons)

It’s hard not to laugh as Ely goes through these intense internal crises over Maangozid’s salvation when its clear the spurned chief has other motives for learning about the faith. In the end, Maangozid tells Ely that he realizes the people still love him, and he resumes his position as Mide leader. This is just one example of Maangozid’s personality coming through the pages.

If you’re scanning through some historical writings, and you see his name, stop and read because it’s bound to be something good. If you find a time machine that can drop us off in 1850, go ahead and talk to Chief Buffalo, Madeline Cadotte, Hole in the Day, or William Warren. The first person I’d want to meet would be Maangozid. Chances are, he’d already be there waiting.

Anyway, I promised a family tree and here it is. These pages come from Kitchi-Gami: wanderings round Lake Superior (1860) by Johann Georg Kohl. Kohl was a German adventure writer who met Maangozid at La Pointe in 1855.

LEADERSHIP OF THE PEMBINA CHIPPEWA NATION

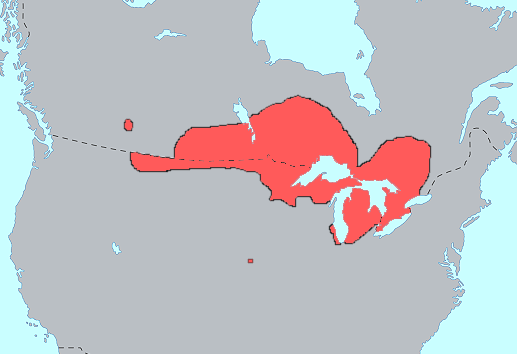

The Wazhazha Mdewakanton of the O'Jibway Nation is ceremonial. The O'Jibway Nation traces back 2000 years as a collection of Nations who unified and worked collectively to establish trade, and family unity, among the Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabemowin, and Algonquin descendants of the Great Lakes. Ojibwa, also spelled Ojibwe or Ojibway, also called Chippewa, self-name Anishinaabe, Algonquian-speaking North American Indian tribe who lived in what are now Ontario and Manitoba, Can., and Minnesota and North Dakota, U.S., from Lake Huron westward onto the Plains. These matrilineal-patrilineal lines merge with one family.

23. Private User

22. GICHI AY'AA OGIMAA MA'LINGAAN ALBERT DENNIS LAMBERT

19. Little Shell III, Ayabiwewidang “Sits and Speaks ” (1872-1903) --->Turtle Mountain Branch Separation and leadership went to Chief Joseph Kaishpa "The Elevated One" Gourneau

19. John Baptiste Brunelle --->Pembina Chippewa Tribe Separation and leadership went to Patrice Francis Brunelle

18. Little Shell II Way-ke-ge-ke-shig (1813-1872)

18. Joseph Montrielle, Warrior of Pembina

17. Chief Makadeshib Black Duck (1811-1813)

17. Joseph Lenau, Tabasnawa Little Shell II (1790-1804)

16. Chief Little Shell I, Standing Firm

15. Chief Gay Tay Menomin Old Wild Rice

14. Chief Kaŋgidaŋ Mdokečiŋhaŋ, Little Crow I

13. Chief Delonaise Atetaŋkawamduška Wáȟpe Šá

12. Waubojeeg

11. King of the Loons Mamaangĕzide

10. Chief Ka-che-ne-zuh-yauk Kahdewahbeday Broken Tooth

6. Wajawadajkoa

5. Wajki Weshki

3. Mitiguakosh

1. Chief Gijigossekot Great Thunderbird

O'Jibway Nation Ogimaakwe: Marguerite Ah-Dik Songab Okicheta Bottineau daughter of Wazhazha Mdewakanton Dakota Grand Chief Chief Delonaise Atetaŋkawamduška Wáȟpe Šá; sister of Red Bear Miscomaquah, son of Bajasswa II, The Dry One

| 1727 |

1727

|

La Pointe, Ashland County, WI, United States

|

|

| 1739 |

1739

|

La Pointe, Ashland County, Wisconsin, United States

|

|

| 1740 |

1740

|

The Hair Hills, The Turtle Mountains, Canada

|

|

| 1747 |

1747

|

Chequamegon, Bayfield, Wisconsin

|

|

| 1775 |

1775

|

||

| 1792 |

1792

Age 65

|

Chequamegon Bay, Wisconsin, United States

|